- Home

- Linwood Barclay

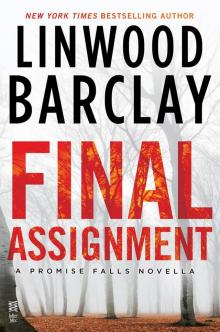

Final Assignment: A Promise Falls Novella

Final Assignment: A Promise Falls Novella Read online

Final Assignment

A Promise Falls novella

Linwood Barclay

Contents

Title Page

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Extract from BROKEN PROMISE

Also by Linwood Barclay

Copyright

One

‘Come on, let’s go into the woods and look around!’ said Charlie, swinging the baseball bat around, banging it on trees as he walked by them.

‘I don’t know,’ said his friend Martin. ‘I don’t like it in there. It always creeps me out! Let’s stay out here by the road.’

‘Just a little ways. Far enough in so we can see cars go by but they can’t see us.’

‘Well, okay,’ Martin said.

They walked more far into the woods. Then Charlie stopped and turned around to look at Martin right in the face and he said all angry-like, ‘So why did you go out with my girlfriend Katherine?’

‘What? What are you talking about?’

‘I know you and Katherine have had something going on. You went behind my back. I saw you guys making out!’

‘That’s bullshit, man. I would never do that. You’re my friend!’

‘Oh yeah?’ said Charlie. ‘I don’t think so.’

He swung the bat and hit Martin right in the head. BANG!

‘Ow!’ Martin yelled. ‘That hurts!’

Charlie hit him again and Martin fell down on the ground. Charlie kept swinging the bat at Martin’s head, breaking open his skull and—

‘What do you think?’

I looked up from the laptop. ‘I’m sorry?’ I said.

‘What do you think?’ Greta Carson asked. ‘Don’t you think it’s well written?’

‘I’m not really a judge of literature,’ I said. ‘I don’t see any spelling mistakes, if that’s what you mean.’

Greta’s son Chandler said, ‘The computer finds those and fixes them.’

‘Please,’ Greta said, putting a hand on her son’s knee, as if that was where his mouth was and she was shutting him up. ‘Mr Weaver doesn’t care about those things. What matters is the story. Isn’t that right, Mr Weaver?’

I’d only been here ten minutes and already had a feeling I didn’t want this case, whatever this case turned out to be. Based on what she’d told me over the phone, I would have turned it down, but she’d gotten my name from an old friend of my wife’s, so at the very least I felt I had to come out here.

I folded down the lid of the laptop and looked at the pair of them. Ms Carson was in her late forties, stick-thin, her black hair molded tightly to her skull, pulled to the back of her head and spun around into something that looked like a small cinnamon bun. She wore a black silk blouse and expensive jeans, a small, tasteful strand of pearls at her neck.

Her sixteen-year-old son Chandler had a sense of style too. Huge white unlaced sneakers that made him look something like a Clydesdale, jeans and a pullover sweatshirt emblazoned with three letters – PFH, which stood for Promise Falls High, where Chandler attended the eleventh grade. His mother had told me before I got here that he was relatively new to the school. He’d spent the previous two years at Claxton Academy, which was private.

‘I think it’s a basic problem with the public school system,’ Greta Carson told me on the phone. ‘They’re not into thinking outside the box.’

Chandler’s short story, of one kid beating another kid to death with a baseball bat, was evidently innovative thinking.

Her call had led me here, to this classic Victorian three-story house in one of Promise Falls’ more upscale neighborhoods. I’d only been back in town a few months, having spent the last decade or more in Griffon, north of Buffalo, and had been reacquainting myself with the various parts of the town that I’d known better back in the days when I patrolled them in a black-and-white.

Sitting here, in the Carsons’ living room, I said, ‘Why don’t we start back at the beginning?’

‘You don’t want to read the whole story?’ Greta Carson asked.

‘Maybe later,’ I said. ‘I’m guessing what matters are is the issues surrounding it.’

‘It’s a freedom of speech issue, that’s what it is,’ she said.

‘Jeez, Mom, do we have to make such a big deal about this?’ Chandler said. ‘Can’t I just be suspended for a few days and we let it go at that?’

‘No!’ she said adamantly. ‘Just when Chandler’s showing signs of initiative, that’s when they come down on him like a ton of bricks.’

‘The beginning?’ I said, hoping at some point to get the woman on track.

She took a deep breath, a signal that her telling of this would be anything but a short story.

‘Chandler’s English teacher, Ms Hamlin, asked the class to write something creative, imaginative. So Chandler applied himself and wrote this story’ – she tapped the closed laptop – ‘and now he finds himself being treated like some sort of psychotic degenerate.’

‘I take it the suspension didn’t happen just like that?’ I said.

‘There was a meeting,’ she said. ‘I was called down there, yesterday.’ She made it sound as though she’d been summoned to a thrift shop to choose a new wardrobe. ‘There was Ms Hamlin, and the head of guidance, what was her name?’

‘Ms Brighton,’ her son said. ‘Lucy Brighton. She was the only one I felt was on my side.’

‘And the principal, Ms Caldwell, was there too. This is what happens when you have too many women in charge,’ Greta Carson said. ‘They think all literature should be Eat, Pray, Love – which, by the way, I liked very much, but not everyone wants to read that kind of thing.’

‘So what happened at the meeting?’

‘Ms Hamlin,’ Greta said, ‘had a case of the vapors, I gather, when she read the story. She took it straight to the principal. She never gave him a chance to read it out to the class, where his classmates would no doubt have found it to be a very engaging story. Ms Hamlin and the others wanted to know why Chandler would write something like that.’

I looked at the boy. ‘Why did you write something like that?’

He shrugged. ‘I don’t know. Why does anybody write anything?’

‘Exactly,’ his mother said. ‘How does one explain the creative process?’

‘Yeah, that’s right,’ Chandler said. ‘The idea just came into my head and I wrote it.’

‘What was their concern?’ I asked.

‘They thought that if I would write something like that,’ Chandler said, ‘I must be like sick in the head. That I’d go out and actually kill somebody.’

Greta Carson nodded furiously. ‘Exactly. They wanted him to go for counseling or psychiatric testing or something like that. Unbelievable! There are lots of people who write dark and creepy things! My God, if Edgar Allan Poe or H. P. Lovecraft or Stephen King had had the misfortune to go to Promise Falls High, they’d have never had a writing career, because some stupid teacher would have sent them off to be tested and put them on medication. It’s beyond ludicrous.’

‘Have you written a lot of stories like this?’ I asked Chandler.

Another shrug. ‘Not really. This was, you know, kind of a one-off.’

‘But you like to write?’

‘Once in a while.’

‘I think this may be a talent of Chandler’s that is just now rising to the surface,’ his mother said.

The phone rang.

‘Oh for God’s s

ake,’ Greta said, and reached for a cordless phone resting on a table next to the couch. ‘Hello? Oh, hi.’ Her brow furrowed. ‘No, we haven’t seen him at all. Okay. Well, I’m sure it’s nothing. Okay. Listen, I have Mr Weaver here right now, so why don’t I give you a call later?’

‘What was that?’ Chandler asked.

‘Nothing,’ his mother said. ‘Where were we?’

I asked Chandler, ‘What made you write this specific story?’

Again his mother jumped in. ‘Are you saying he was wrong to write it?’

I turned and looked at her as patiently as I could. ‘I’m just trying to get the big picture here.’ I looked back at Chandler. ‘So why did you write this?’

‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘I guess I wanted to bring my mark up in that class.’

‘You haven’t been doing that well?’

‘Not really,’ he said. ‘Ms Hamlin doesn’t like me.’

‘A lot of the teachers have it in for him,’ his mother said quickly.

‘Why would that be?’

Now it was her turn to shrug. ‘I just don’t know.’

‘Have you been in trouble before this?’ I asked Chandler.

‘Um,’ he said.

‘Nothing serious,’ Greta Carson said.

‘What happened?’ I asked.

Chandler grimaced. ‘It really wasn’t that big a deal. Everything’s fine now. We get along and everything.’

I looked at the two of them, waited.

‘Okay, so what happened,’ Chandler said, ‘was me and my friend Mike, we kind of made fun of a guy.’

‘It was harmless,’ his mother said. ‘A prank.’

‘Mike Vaughn?’ I asked. It was my late wife Donna’s friend Suzanne Vaughn who had referred Greta Carson to me. I knew she had a son named Michael.

‘Yes, that’s right. Suzanne’s boy,’ Greta said. ‘We’ve been friends with Suzanne and Elliot for years, and Chandler and Michael have grown up together.’

‘So what was this prank that you and Mike cooked up?’ I asked Chandler.

‘So there’s this guy named Joel Blakelock, and he’s kind of, you know, everybody knows he’s kind of gay, which is fine, right? But there was this thing at school, and he was around back, by the parking lot, and he was sort of making out with some other guy, and me and Mike, well, Mike, he got out his phone and he took a picture of them. You couldn’t see the other guy, but you could tell that it was Joel, and we sort of put it out there.’

‘Out there?’ I said.

‘Like, we posted it. And then everyone else posted it. And Joel got really upset because he kind of thought it was an invasion of privacy and—’

‘They were right out in the open,’ Greta Carson said.

I gave her a look that said, Please.

‘Go on,’ I said to Chandler.

‘Yeah, like he got pretty upset about it, and somebody said he actually was going to kill himself over it but I don’t think that’s true, and Mike and me got in trouble and got suspended for a few days, but then things, like I said, settled down. I’m even sort of like friends with Joel now. Not in a gay way, of course.’ He flushed. ‘But like friends in other ways.’

‘This happened since you’ve been at Promise Falls High?’ I asked. Chandler nodded. ‘And why did you leave the private school?’

‘Oh, that,’ Chandler said.

‘The school failed to meet Chandler’s academic needs,’ his mother said. ‘So we moved him out.’

‘We?’

‘My husband Malcolm and I.’

‘Where is Mr Carson?’ I asked.

‘He’s at work.’

‘What’s he do?’

‘He’s a financial consultant,’ she said. ‘He used to teach business, but then he actually got into it. Those who can do, you know.’

‘Does he know you called me?’

She swallowed. ‘I’ll be bringing him up to speed soon enough. And I hardly need my husband’s permission to engage someone’s services. That’s a very sexist attitude.’

‘My apologies if that’s how it came across,’ I said. I needed to get things back on track. ‘What did you mean, the school did not meet Chandler’s academic needs?’

‘They weren’t challenging him enough, and as a result, his grades suffered.’

Back to Chandler. ‘You were failing and they dropped you?’

‘Kinda,’ he said.

‘That’s not how I would characterize it,’ his mother said. ‘So, regrettably, we had to move Chandler to the school in our neighborhood. I think that’s why the teachers are against him, that he came from a private school. There’s a kind of reverse snobbery going on, if you ask me.’

‘I see,’ I said. I put my hands on my knees, getting into position to stand and walk out of here. But I at least had to ask. ‘Just how were you thinking that I might be able to help?’

‘I want you to get those school officials to change their minds and end this suspension, drop their demands that Chandler see someone for this ridiculous psychiatric help, and apologize.’

I shook my head. ‘You’ve got the wrong guy. If anything, what you want is a lawyer. Not a private detective.’

‘No, you’re exactly what I need,’ Greta Carson said. ‘I want you do dig up some dirt on the school.’

Chandler’s eyes rolled toward the ceiling. He sagged back into the couch, looking as though he hoped the cushions might swallow him whole.

‘Excuse me?’ I said to his mother.

‘It’s a big school, lots of staff. I’m sure some of them have done something they wouldn’t want everyone else to know about. Start at the top, with the principal. Maybe she sleeps around. Or that guidance counselor. I hear she has a weird daughter, some kind of learning disability or something. Good heavens, don’t make me do the work for you. This is your area. This is what you get paid for, isn’t it? Dig around and see what you find.’

‘To what end?’

She laughed. ‘Seriously? Once you’ve got something on them, I’m sure they’ll be much more amenable to dropping this whole business with Chandler.’

‘You want to blackmail your son’s teachers so they leave him alone?’

‘I wouldn’t put it that way,’ she said. ‘I’d think of it as leverage.’

I stood.

‘It’s been a pleasure, Ms Carson.’ I smiled, nodded, then turned to Chandler. ‘Good luck with your writing career.’

As I moved toward the door, the woman trailed after me. ‘Aren’t you going to help us?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘Although I think there’s no doubt you need help, Ms Carson.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’ Greta Carson asked.

I let myself out.

I popped in to say hello to Naman on the way up to my apartment. I was renting a place over his used bookstore, and he was my landlord. He was sitting behind the counter reading an old Bantam paperback edition of a Nero Wolfe novel by Rex Stout when I walked in.

‘How’s it going?’ he asked.

‘Okay,’ I said.

‘You are on a case?’ he asked, grinning. He read a lot of detective fiction and thought what I did for a living was exciting and glamorous. I wished.

‘Turned one down,’ I said.

‘A divorce case?’ he speculated. ‘You don’t do that kind of work because it’s too messy?’

‘Something like that,’ I said.

There was a door off the sidewalk, next to the entrance to his shop, that led up to my place. I trudged tiredly up the stairs, took off my jacket and threw it over the back of a chair, loosened my tie. I opened the fridge, surveyed the contents, and decided it would be tricky to whip up something interesting for dinner with only milk, olives, and strawberry jam.

My cell phone rang.

I found it in my discarded jacket, glanced at the call display.

VAUGHN.

That would be Suzanne Vaughn. I was betting Greta had phoned her to complain that the private invest

igator she’d recommended so highly had refused to take her case, and insulted her to boot.

I took the call.

‘Hello.’

‘Cal?’

‘Hi, Suzanne. Greta must have called you.’

‘What? No, she didn’t.’

‘Oh. I thought she might have.’

‘That’s not why I’m calling,’ she said. I noticed, now, an edge in her voice.

‘What’s wrong, Suzanne?’

‘It’s Michael. He hasn’t come home. We haven’t seen him since last night. Elliot and I are absolutely frantic.’

Two

I drove straight over to see Suzanne and Elliot Vaughn. They lived only a few blocks from the Carsons, but this was a different neighborhood. Not that the homes here weren’t nice, but they were more modest – a hundred thousand per house more modest. The Vaughns lived in a one-story house with clapboard siding. The lawn needed some attention, and from the street I could see part of an old rusted swing set in the backyard that didn’t look as though it had been used in years.

Suzanne and my wife Donna had gone through high school together and kept in touch during the years that we had lived in Griffon. Suzanne and Elliot had been among the few from Promise Falls who had come to Griffon for Donna’s funeral.

Suzanne, a short, tiny woman who had always reminded me of a sparrow, had been watching for me and had the door open before I reached it.

‘Cal, thanks for coming.’

‘Have you heard from him since you called me?’ I asked.

She shook her head furiously. ‘I keep trying his cell but he’s not answering.’ She turned her head and called into the house. ‘Elliot! Cal’s here.’

Elliot appeared from the kitchen as I entered the house. He offered a hand and I took it. ‘Thanks for coming,’ he said. He was a small man, maybe five-two, and he hadn’t had any hair since he was in his early twenties. I’d often wondered if he’d married Suzanne because she was the only girl he could find who was smaller than him.

‘Have you called the police?’ I asked.

‘No,’ he said. ‘I’m not so sure we need to bring them in.’

‘He stopped me,’ Suzanne said, almost accusingly. ‘I’ve been wanting to call them since three in the morning.’

‘He’s a teenage boy,’ Elliot said. ‘Teenage boys do stupid things. Maybe he’s with a girl, or had too much to drink and he’s sleeping it off somewhere.’

Chase

Chase No Time for Goodbye

No Time for Goodbye Far From True

Far From True Lone Wolf

Lone Wolf Fear the Worst

Fear the Worst Broken Promise

Broken Promise A Tap on the Window

A Tap on the Window Parting Shot

Parting Shot Bad News

Bad News Too Close to Home

Too Close to Home Final Assignment

Final Assignment No Safe House

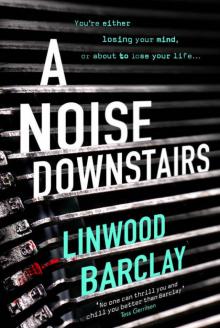

No Safe House A Noise Downstairs

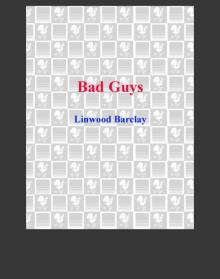

A Noise Downstairs Bad Guys

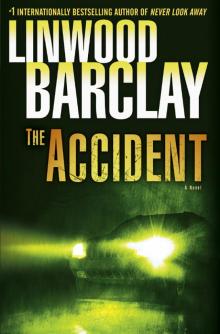

Bad Guys The Accident

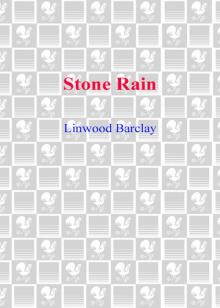

The Accident Stone Rain

Stone Rain Elevator Pitch

Elevator Pitch Bad Move

Bad Move Clouded Vision

Clouded Vision Never Saw It Coming

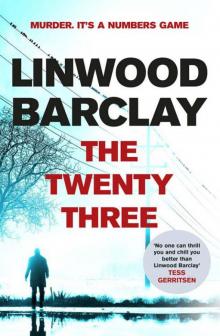

Never Saw It Coming The Twenty-Three

The Twenty-Three Find You First

Find You First Never Look Away

Never Look Away Elevator Pitch (UK)

Elevator Pitch (UK) Stone Rain zw-4

Stone Rain zw-4 Bad News: A Zack Walker Mystery #4

Bad News: A Zack Walker Mystery #4 Lone Wolf zw-3

Lone Wolf zw-3 Final Assignment: A Promise Falls Novella

Final Assignment: A Promise Falls Novella Bad Guys zw-2

Bad Guys zw-2 Never Saw It Coming: (An eSpecial from New American Library)

Never Saw It Coming: (An eSpecial from New American Library) Never Look Away: A Thriller

Never Look Away: A Thriller Broken Promise: A Thriller

Broken Promise: A Thriller Bad Move zw-1

Bad Move zw-1 The Twenty-Three 3 (Promise Falls)

The Twenty-Three 3 (Promise Falls)